She was running marathons, then she could barely move:“It felt like someone threw me off a cliff.”

The picturesque village of Cooperstown, New York, is anchored by Otsego Lake, where tourists take pleasure cruises and avid runners enjoy a 21-mile path that winds around its bucolic shores, past landmarks like Glimmerglass State Park and the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Long after the local marathon season in 2013, Mary-Margaret Robbins had kept up her regimen of 10 miles per day and double the distance on weekends — just another part of her busy days as a pharmacist, mom of a toddler and wife to her high school sweetheart.

By late September, however, the usually energetic 38-year-old was stopped short by distress signals from her own body.

“I went from running 22 miles on weekends to not being able to walk up four steps or 200 feet to the coffee shop without having to stop,” Robbins, now 44, told TODAY. “It was like someone threw me off a cliff.”

Within a couple of weeks, she had slowed down across the board. When she took her 2-year-old daughter, Maggie, to an urgent care clinic for an ear infection, Robbins asked the doctors to examine her, too.

She described a crippling fatigue, unexplained pains and that something seemed wrong with her heart. The clinic doctor diagnosed her with a sinus and ear infection and prescribed a course of the antibiotic amoxicillin.

After more than a week on the medication, Robbins hadn’t improved and a full suite of symptoms began to show.

“Something’s not right,” she told the clinic doctor. “My ear is in pain, my depth perception (is off), I’m having roving pains — and I can’t run.”

The complications that seemed to rise suddenly were harder to explain because they were invisible to the casual observer; Robbins looked perfectly healthy, maybe just a little tired, even in her own reflection.

“Nobody would believe it because I always looked so good,” she said. “It’s hard if you don’t look sick or act sick because you want to put on a brave face.”

Inside, however, her body just wasn’t responding and Robbins was sure something serious had taken hold. The clinic didn’t believe it could be another infection, but they had no other answer.

For a second opinion, she visited her primary care physicians’ group where she explained her increasing symptoms and what seemed like heart problems such as faintness, very low heart rate and irregular heartbeats.

“It’s hard if you don’t look sick or act sick because you want to put on a brave face.”

A few years earlier, her husband, Matt Sohns, had cardiac arrest and Robbins knew some of the signs. She had one of his heart rate monitors at home and tested herself by cycling to her limit on a spin bike. Runners often have lower heart rates, but by most measures, Robbins’ active rate should have read between 90 and 180 beats per minute during cardio exercise. However she tried, she couldn’t get it out of the basement: 45 bpm, 47 bpm.

Her primary care group’s response came as a shock. She said they didn’t believe her heart rate could be so low, questioned her mental health and treated her like a “stupid woman.”

“They said, ‘You’re depressed,’” she recalled. “They wanted to give me an SSRI or Celexa.”

As a pharmacist, Robbins knew a possible side effect of the meds could prolong the time her heart took to recharge between beats. In her state, she feared that would lead to sudden cardiac death and refused them.

Meanwhile, she was suffering more every day with irregular heartbeats, an “atrial knock” in her heart that kept her up at night, traveling pains and increasing exhaustion.

She started asking for specific tests at the office: a Lyme test, for which the first part came back positive, and an electrocardiogram, or EKG, to find out what was wrong with her heartbeat, which she wasn’t given.

“They said, ‘Your heart is strong, it’s fine,’” Robbins continued. “I said, ‘I need help, I’m going to die in the middle of the night.’”

Halloween had arrived and Maggie was all dressed up. Robbins wanted so much to take her trick-or-treating in the neighborhood, but she couldn’t muster the strength. Maggie went with her dad instead. It was a grim snapshot for Robbins and a wake-up call that she desperately needed help.

A turning point came when she decided to see a private cardiologist, Dr. Anthony Cammilleri in nearby Oneonta. For the first time, she felt her complaints were taken seriously. After he gave her an EKG, a stress test and a battery of evaluations, he confirmed that her heart’s electrical system was unable to conduct enough signals to beat properly.

“He told me, very calmly, ‘Good God, you’re in complete heart block,’” Robbins said.

Cammilleri sent her immediately to UHS Wilson Medical Center, a hospital about an hour away, where another test for Lyme came back positive on both parts. Combined with the heart block, the hospital team diagnosed Robbins with Lyme carditis. She received oral and IV antibiotics meant to kill the tick-borne bacteria, called Borrelia, raging through her system.

The situation had gone on for weeks, maybe months, before she was diagnosed, however. It would be no easy feat to reverse the damage already done by an unchecked Lyme infection.

She was sent home to continue on the IV line, in hopes her heart would recover.

“He told me, very calmly, ‘Good God, you’re in complete heart block.’”

Lyme carditis is “an extraordinarily rare complication” of Lyme disease, Dr. Paul Auwaerter, clinical director, division of infectious diseases at The Johns Hopkins Hospital told TODAY.

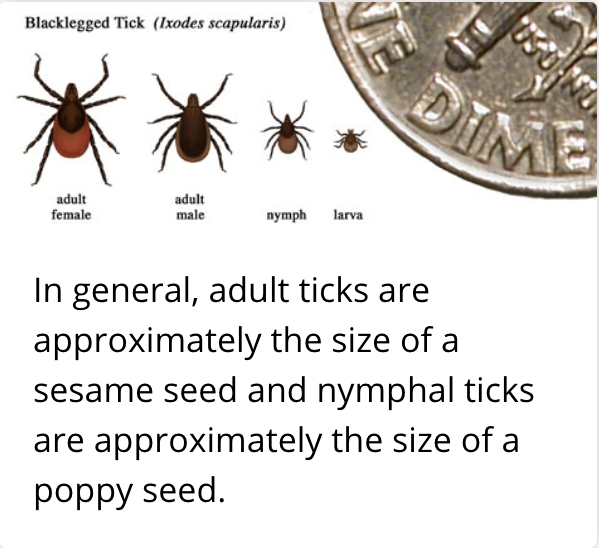

The complication occurs when Borrelia bacteria transmitted from an infected black-legged tick travel through the bloodstream and infect the heart. The longer an infected tick feeds on a human, the higher the chance of Lyme disease — and the more time passes before Lyme is treated, the greater the chance the infection can cause irreversible damage to organs, including the heart.

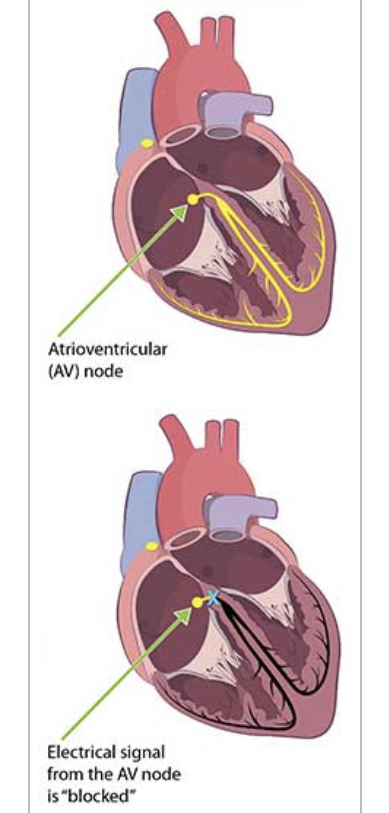

Heart block — like Robbins’ — occurs when the toxic bacteria disrupt the atrioventricular, or AV, node that conducts electricity between the upper and lower heart chambers. The problem can be fatal.

Only about 1% of Lyme disease patients are estimated to have Lyme carditis, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Some studiesplace the likely numbers of Lyme carditis cases higher. Exact numbers are hard to assess because people with Lyme disease may not be tested for heart complications and those with heart block or other conditions may not be tested for Lyme. Several of the known cases have been diagnosed by autopsy.

Lyme disease has exploded in the last couple of decades and also expanded to more areas. The CDC estimates about 300,000 people are infected every year with Lyme disease — the most common disease transmitted to humans from mosquitoes, fleas and ticks.

The burden of Lyme disease on American healthcare is also increasing; the CDC places the cost of testing alone at $492 million per year. No official estimates have yet been made on the growth or healthcare cost of Lyme carditis.

Auwaerter, who is not involved in Robbins’ care, researches Lyme disease and has consulted with the National Institutes of Health and Food and Drug Administration about the disease. He believes Lyme disease is spreading because of a variety of factors including reforestation, growing deer populations, people migrating more to suburbs and climate change.

In places where Lyme disease has just begun to spread, doctors and patients may not think about testing for the infection, which can then delay critical early treatment.

“Because, historically, these communities didn’t really have it,” Auwaerter said. “We have to be vigilant … so that when new communities are affected the doctors and healthcare providers are aware.”

The invisible nature of early Lyme disease is the most urgent and dangerous problem. It can hide well for weeks and the only prevention is manual: checking for ticks and removing them before they feed too long.

No vaccine has been found safe and effective and it takes several years to research and receive FDA approval on anything new. But, scientists are focused on developing immunity as a primary tool in the fight against Lyme.

“After many years of lack of research, there’s more research in developing a Lyme vaccine that would be helpful and protective for acquiring Lyme disease,” Auwaerter said. “I would say that’s probably fundamental.”

Though current treatment options for Lyme disease — generally a cycle of antibiotics like doxycycline, amoxicillin or ceftriaxone — are highly effective when the infection is caught early, that often doesn’t happen.

Identifying Lyme disease remains a major challenge. The red “bullseye” rash that can be a telltale sign only appears some of the time. The current Lyme test is also far from foolproof; it doesn’t read the amount of Borrelia bacteria, only the antibodies the blood makes in response to fighting them, which can take weeks to build up.

Researchers are working on creating better Lyme tests than the only one currently FDA-approved, according to Auwaerter:

“The idea is: Are there tests that are more helpful at making a very early diagnosis of Lyme disease or that are very effective at ruling out Lyme disease?”

In Robbins’s case, she never saw a tick and never had a bullseye rash. The many weeks, maybe months, between when she was bitten by a tick and when she received targeted treatment gave the bacteria ample opportunity to short-circuit her heart.

“My little girl thinks she’s going to go to the church Christmas pageant with her mother…”

Credit: Mary-Margaret Robbins.

Three deaths from Lyme carditis were reported by the CDC in 2013. Robbins read about their cases the day before Christmas Eve and said, “Oh my God, I don’t want to be the fourth.”

She went back to Cammilleri and said she wasn’t feeling any better after a month of antibiotic treatments. He told her the heart block was irreversible and she was in a dangerous situation. Paramedics took her back to the hospital immediately; she needed a pacemaker to help her heart beat.

Because it was a holiday and nobody nearby was qualified to perform the surgery, Robbins was sent in an ambulance on an 8-hour journey from upstate New York to Cleveland Clinic in Ohio. The hardest part was knowing she had to leave her daughter waiting at home, unsure of what would happen.

“My little girl thinks she’s going to go to the church Christmas pageant with her mother,” she said. “But her mother’s not home, she’s fighting for her life.”

On Christmas Day, an assessment at Cleveland Clinic confirmed that Robbins was in complete heart block related to Lyme disease, which had not responded to the usual antibiotics.

The report said, “…the delay in diagnosis and lack of improvement to date mean that her response is lower than most patients. She has significant symptoms and her life has been disrupted…”

Robbins received the pacemaker the day after Christmas in 2013. For the first time in months, she could catch her breath and walk a little longer.

But, it wasn’t long before she had complications. Robbins went through a few pacemakers because they had to work so hard that the batteries kept dying. She also had problems with placements and felt one had pierced her heart tissue. Finally, she started searching for different treatment options.

In December 2017, she saw a team specializing in complex heart arrhythmias at Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, New York, where Dr. Jorge Romero recommended an external defibrillator and later a device called an ICD. Though it helped, Robbins was still unable to regain her normal function. The next year, she was recommended for a heart transplant.

She was directed to the transplant team of Dr. Mark Zucker and Dr. Margarita Camacho at Newark Beth Israel Medical Center, who assessed her in fall 2018.

“Her quality of life was awful. For a marathon runner? She had shortness of breath with just one flight of stairs, she had to stop walking after just one city block,” Camacho, surgical director of cardiac transplantation and assist devices for Newark Beth Israel Medical Center told TODAY. “A young woman like this, she was only 43 when I saw her … especially when you’re used to being so athletic.”

“I didn’t want to lose my heart.”

Credit: Mary-Margaret Robbins.

Robbins was put on the waiting list for new hearts and her life was put on hold. Like everyone on the list, she kept a “go-bag” packed and had to remain in the orbit of the hospital in case she was called at any moment.

The wait can go on for years, but not this time. After two months, Robbins was preparing for a close friend’s burial service when she had a vision of the friend handing her a white box with a red ribbon. She said it was then that Sohns walked towards her with a phone in his hand and told her the hospital was calling. They had a strong matching heart, Robbins remembers a nurse saying, and she had to come to Newark right away.

She found Maggie, who had watched her mother’s struggles for five years, downstairs coloring and told her, “They have a heart for me.” The little girl, then 9, just cried.

On March 3, 2019, at 3 a.m., Robbins had the heart transplant that Camacho, who performed her surgery, described as very successful. Within a couple days, she felt better than she had in years and was released from the hospital after two weeks. The beginning of this new chapter made her realize how limited her past few years had been.

“I have a lot to give, a lot left to do and I’m just trying to do that every day.”

Before she contracted Lyme, Robbins said she was hardly ever sick and felt she was giving back to her community as a practicing pharmacist.

“I was always taking care of my body, I worked hard, I was helping people,” she said.

Her life is different now and she’s trying to “reinvent” herself. Because she’s on immune-suppressing drugs to prevent her body from rejecting her new heart, Robbins can get sick very easily. She can no longer work in a hospital or community pharmacy setting because the risk would be too great. As for running, Robbins knows she won’t be in a marathon anytime soon, but she’s been walking and even jogging a little.

After all she’s survived, though, Robbins is grateful to be with her husband and family and watch her little girl grow up.

“I am so happy to be here for my daughter, she went through so much,” Robbins said. “Just the other day she said, ‘I’ll never forget when you left, Mommy, I went in your bedroom and I saw the toothbrushes were gone and I started crying.’ I just realized the burden that she carries.”

She’s trying to help her community in a different way now, by working with kids and refugees through a tennis program. She also wants to be an advocate for gender and racial equality in heart disease treatment.

“Hopefully, I’ll find my spot,” Robbins said. “I have a lot to give, a lot left to do and I’m just trying to do that every day.”

She also hopes people who show any symptoms of Lyme disease will follow their instincts and push to get help from Lyme-literate doctors. She credits Cammilleri for the diagnosis that helped save her by leading to appropriate treatment and Zucker’s team for giving her another chance at life through the transplant.

“I didn’t want to lose my heart, who does?” Robbins said. “But someone decided to help me.”