“The world is on track to lose up to 90% of its coral reefs within the next 30 years,” the U.N. says.

For NBC News/TODAY

The first Atlantic Ocean coral species born through a technique called “induced spawning” has ignited hope for a new path to help the world’s suffering coral reefs.

“This is the first major step at the bottom of a very tall staircase,” Keri O’Neill, senior scientist at The Florida Aquarium in Apollo Beach, Florida, and a leader of the induced spawning initiative called “Project Coral,” told TODAY.

The pillar coral produced through the assisted reproduction effort is listed in the Endangered Species Act. The finger-like species has not been able to spawn successfully in its native environment on the Florida Reef Tract — where the coral die-off has been so severe, only about 6% of the reef is covered by living coral, down from a height of 33%, a recent study found.

Worldwide, coral reefs have been ravaged by a combination of warming oceans, man-made pollution and coral disease.

The largest in the world, Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, was recently downgraded to “very poor health” after massive coral “bleaching” and die-off in the last few years.

“Without urgent intervention, the world is on track to lose up to 90% of its coral reefs within the next 30 years,” the United Nations estimated in a report.

Enter science: Marine biology researchers around the globe have been working to protect and repopulate reefs by helping endangered corals — which only spawn once a year in the wild and don’t always produce offspring — breed more successfully in labs.

The push to save coral reefs that support millions through science

Coral biologists have two major priorities: protecting reefs that are still thriving and working to restore the many damaged coral reefs, in part by helping corals reproduce.

“We have to address the coral reef problem from a lot of angles, all over the globe,” Michael Fox, a coral reef ecologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, who was not involved in the new research, told TODAY.

“We need to make sure that we are protecting these naturally resilient or still-healthy coral populations in the wild,” he added, “while also still focusing on trying to bring back the ones that have been hit harder from other threats.”

Millions of people depend on coral reef environments. The bleak outlook for the world’s reefs spells economic, as well as ecological disaster to both people and ocean life. Coral reef environments provide an estimated $29.8 billion globally in revenue from tourism, commercial fishing and more. U.S.-based fisheries associated with coral reefs account for more than $100 million in commercial revenue.

They are also a lifeline, providing coastal communities with a continuing source of food and protection from severe floods and storm surges.

The Florida Reef Tract — the world’s third-largest shallow-water barrier reef, which spans about 360 miles from South Florida to the Dry Tortugas in the Caribbean — houses some coral species so decimated the surviving members are too isolated to make babies in the wild.

An epidemic of stony coral tissue loss disease broke out in 2014 and has spread rapidly. The coral have also been hurt by warming ocean temperatures and a host of man-made pollution: runoff from commercial fertilizer causing algae blooms, large amounts of untreated sewage spewing into the sea as the population has grown and dredging to expand Miami harbor, which coated parts of the reefs with sediment.

A partnership of scientists, led by NOAA and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission, including The Florida Aquarium, has been working to rescue and preserve 22 threatened coral species from the tract.

The ‘fertility clinic’ for coral

Setting the mood for corals to spawn, or release their eggs and sperm into the water for fertilization, is no easy feat. Corals are sensitive animals that are very particular about their environments and most breed only once a year. An increasing number have been unable to breed at all.

Induced spawning, which can be completely controlled in a lab where the corals are protected from harsh environments, could help regenerate endangered coral species to restore dying reefs anywhere.

“In the wild, you may only get one or two individuals that survive from a whole spawning event,” O’Neill said. “By putting 15 different individuals all together in a tank, where they’re contained, and then triggering it to spawn, we can actually make tens of thousands of offspring all in one year.”

Corals read cues from the environment over the course of the entire year — the sunset times, moon phases, seasonal temperatures and more. Induced spawning is carefully orchestrated to mimic all the fluctuations.

“Getting the environmental cues to convince corals to spawn in the lab is quite difficult,” Fox said. “I think it’s a great advance in the world of just basic coral biology, but also restoration, because it’s going to help us actively study and learn more about coral species that are in such low numbers in the wild.”

The technique, pioneered by The Horniman Museum and Gardens in London, was used to help 18 species of Pacific corals spawn in years prior. The Florida Aquarium hoped to replicate that success with endangered species of Atlantic Ocean coral.

However, they didn’t know if it would work for the pillar coral species they had rescued from the Florida reefs.

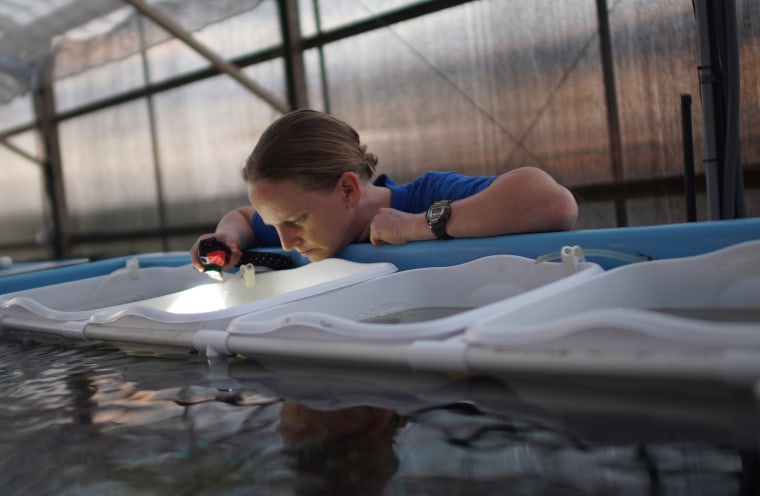

Last year, the process — and the long waiting game — began. Researchers placed the rescued coral, which had been in the aquarium so long they no longer had any sense of the natural environment, into the induced spawning chamber. The chamber was calibrated to simulate the cues pillar coral follow in nature.

“They’re getting no natural sunset or temperature cues, it’s all reproduced artificially, but it’s programmed to mimic the wild,” O’Neill said, “using technology and programming and LED lighting.”

Success arrived in mid-August. The rescued pillar corals had taken the artificial cues and spawned two days in a row, right on schedule. The pillar coral on the Florida reefs have been unable to reproduce because there are too few remaining for fertilization. But, in the induced spawning chamber, it worked.

The endangered pillar coral produced many fertilized larvae, which are now coral babies living in The Florida Aquarium’s coral nursery.

“We have a lot of coral babies,” O’Neill said. “Once they are big enough, we will hopefully be able to start looking at some [transplanting] or release projects, where we start putting them back into certain areas, and study their survival.”

The future for coral reefs

Eventually, the research team hopes some coral species can learn to spawn more than once a year, through the artificial cues of induced spawning. This could help repopulate dying reefs a little faster.

But, it would still take years from the time of spawning to the point where adult coral could be transplanted back onto a reef. In the meantime, coral living in the ocean remain vulnerable.

“None of this is going to change overnight.” O’Neill said. “Our oceans are not going to become clean and stable and climate change is not going to go away anytime soon.”